Well, I guess the NPR shoe I’d been warned about has dropped, with respect to the cancellation of BPP.

It was not a satisfying thud.

The comments on the BPP blog site, reacting to the memo, have begun rolling in. They are not, one would expect, positive. There’s some respectful language in there, but the overall feeling is that this formal response missed the point(s).

My own comment, submitted to NPR (and it may be up by the time you read this):

For all those saying NPR should have raised money directly for BPP, there’s a political mess you’re not aware of here.

If NPR openly attempted to raise money for any program, with large or small station carriage, the nationwide collection of stations would revolt. And please note the Board of NPR is majority-controlled by stations.

In short, it would never be attempted and would certainly be killed if it were.

There are indeed structural and cultural problems within NPR that make a project like BPP fail and put all forms of new media engagements at risk. But never forget that many of NPR’s most anti-new media anti-innovation qualities are inherited from the codependent relationship with the stations. In a sense, it’s no one’s fault, yet it’s everyone’s fault. And that’s the center of the problem.

The entire system is trapped by its own success in the radio medium — not the web. Asking it to change in fundamental ways (e.g. embracing direct funding, using the web innovatively and as a medium of first resort, building real community) is asking for a revolution in which heads would most certainly roll.

But public radio has not historically been a head-rolling collection of institutions.

If you want to change public media for the better, focus on your local station — volunteer, get on the Board, ask tough questions, demand new services, and prove to your station there’s money to be saved and made in engaging the community in new ways, especially online. And tell your station to let NPR grow and mature — even if that means audiences want direct relationships with the network rather than the station. Local stations need a reason to exist beyond rebroadcasting NPR anyway. It’s time they learned how to be local (again).

Or, failing all that, strike out on your own and create a new media entity with the soul of a public radio station but the structural DNA of a Google.

There’s a future for public media, to be sure. But only time will tell whether NPR will participate in it fully and faithfully.

Naturally, I have more thoughts, but didn’t want to post them at NPR’s site.

Overall review of the memo? Disappointing.

Haarsager’s memo language does not, as so many commenters already noted, ring true. There’s something wrong here; something out of place.

Canceling BPP doesn’t bother me per se (this kind of thing happens from time to time for many reasons, and BPP was cursed with bad luck from the start). But NPR’s handling of the cancellation has the feeling of political talking points about it, and that won’t fly in a new media era. Words like “misdirection,” “willful ignorance” and “politically convenient” come to mind very easily here, and they shouldn’t. That’s not what I want to think about NPR.

But if you think my take on the situation is harsh, head over to the Huffington Post where Daniel Halloway has his way with the story.

For me, the upshot is that NPR is fundamentally flawed due to the nature of the relationships between stations and network. There’s no long-term-successful way forward unless that flaw is corrected, either by renegotiation of the relationship or by breaking free of the relationships entirely.

While it’s not an exact analog for where newspapers were 10 years ago, it’s close enough: a medium…

- trapped by its own success

- unable to innovate into a new model, even in small ways

- finally dismantled by market forces beyond its control

I really hate this. This isn’t what I want for NPR specifically or public media broadly. Will someone please tell me I’m wrong? I don’t want to lose NPR!

The word is out that a little more than a week after launch, the iPhone 3G is now just plain gone from stores across the U.S. — be they Apple Stores or AT&T stores. Indeed, AT&T was sold out nationwide on the first day. Apple Stores have carried the device intermittently ever since and as of Monday morning there were only 3 stores nationwide that had anything — each carrying only one model.

The word is out that a little more than a week after launch, the iPhone 3G is now just plain gone from stores across the U.S. — be they Apple Stores or AT&T stores. Indeed, AT&T was sold out nationwide on the first day. Apple Stores have carried the device intermittently ever since and as of Monday morning there were only 3 stores nationwide that had anything — each carrying only one model. AOL Radio is pretty simple. It’s direct, live streaming access to the “AOL Radio” channels of music, sort of like satellite radio in that they aren’t local broadcast stations and are organized around tons of musical themes/styles. But it’s also an application that grants streaming access to hundreds of local terrestrial stations in the CBS collection. I can now listen, on the iPhone (with a live WiFi signal) to real-time streams of radio stations from coast to coast.

AOL Radio is pretty simple. It’s direct, live streaming access to the “AOL Radio” channels of music, sort of like satellite radio in that they aren’t local broadcast stations and are organized around tons of musical themes/styles. But it’s also an application that grants streaming access to hundreds of local terrestrial stations in the CBS collection. I can now listen, on the iPhone (with a live WiFi signal) to real-time streams of radio stations from coast to coast. Pandora had interested me before, but only in an intellectual way. Now, presented again on the iPhone for free, I figured I’d try it again. It’s amazing, especially over WiFi. Let me say that again: it’s amazing.

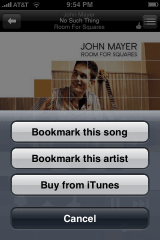

Pandora had interested me before, but only in an intellectual way. Now, presented again on the iPhone for free, I figured I’d try it again. It’s amazing, especially over WiFi. Let me say that again: it’s amazing. I’ve begun discovering music and artists again. I’ve started buying music again. Sunday alone I dropped $30 on new music, buying tracks both from the iTunes Store and from the Amazon MP3 Downloads service. All $30 were spent on artists I’d never experienced before Pandora suggested them and I bought them using links presented by Pandora.

I’ve begun discovering music and artists again. I’ve started buying music again. Sunday alone I dropped $30 on new music, buying tracks both from the iTunes Store and from the Amazon MP3 Downloads service. All $30 were spent on artists I’d never experienced before Pandora suggested them and I bought them using links presented by Pandora. Perhaps I’m already past the age where music radio makes sense for me, but I have to wonder what happens to music radio when this kind of access to music is virtually ubiquitous. Remember — the iPhone 3G sold 1 million devices in the first weekend and is sold out nationwide a week later. Pandora is a free service and free application — no advertising, no tricks — and it’s easy to use. (I began to wonder why I bothered syncing music to the iPhone — why not just live on Pandora recommendations alone?)

Perhaps I’m already past the age where music radio makes sense for me, but I have to wonder what happens to music radio when this kind of access to music is virtually ubiquitous. Remember — the iPhone 3G sold 1 million devices in the first weekend and is sold out nationwide a week later. Pandora is a free service and free application — no advertising, no tricks — and it’s easy to use. (I began to wonder why I bothered syncing music to the iPhone — why not just live on Pandora recommendations alone?) Earlier this week I was advised privately to wait for an announcement from NPR about BPP — without any hint of what said announcement might be — and I’m still waiting. I’d love to hear NPR announce a bold new plan to take the BPP straight to the web and change it up somehow. If anyone would care to shed additional light, I’m all ears (as are about

Earlier this week I was advised privately to wait for an announcement from NPR about BPP — without any hint of what said announcement might be — and I’m still waiting. I’d love to hear NPR announce a bold new plan to take the BPP straight to the web and change it up somehow. If anyone would care to shed additional light, I’m all ears (as are about