Three good pieces of note that I’m finally getting to this evening.

First up (blogged earlier by Todd Mundt) is a take on the Bryant Park Project collapse from someone else that’s young and actually creating public radio programming. Only in this case it’s done on a small scale and is therefore sustainable.

The Sound of Young America‘s Jesse Thorn chimes in on both the BPP and the Fair Game cancellations. He offers lots of insightful commentary (so read the whole thing); here’s one great passage:

Fair Game and especially BPP were designed for a multi-platform future that’s in its earliest stages. Despite speculation to the contrary, both were building very strong podcast audiences. That said, both PRI and NPR are organizations that can’t afford to alienate stations, and that means they can’t really go directly to listeners for money. So the only real option available to them to monetize those online audiences is underwriting, and that’s a pretty modest revenue stream right now. So while both shows were relatively good at online stuff, they weren’t getting much money out of it. Certainly not millions of dollars.

—

Separately, On The Media‘s Bob Garfield is getting a lesson on web comments this week in the wake of the latest OTM show. Garfield went off in the show about web-based comments and commenters, even provoking Ira Glass to refer to him as a “royalist” with respect to how he views comments and the great unwashed masses.

One media commenter and experienced software pro — Derek Powazek — went a step further and wrote two pieces about comments and how they should work, taking Garfield to task for ignoring a long 10-year history of better comments across the web as well as playing the part of Grandpa Simpson.

This is Not a Comment (26 July 2008)

The story completely missed moderation queues, reputation management systems, or any of the hundreds of comment systems built over the last decade to address this very problem. Garfield seems to base the entire story on some bad comments on the OTM site, a site that provides a completely open, no signup required, comment system. But instead of asking “Is there a better way to do this?” he goes for the much easier story: “Gosh internet commenters sure are dumb!”

10 Ways Newspapers Can Improve Comments (28 July 2008)

The real reason comments on newspaper sites suck isn’t that internet commenters suck, it’s that the editors aren’t doing their jobs. If more newspapers implemented these 10 things, I guarantee the quality of their comments would go up. And this is just the basic stuff, mostly unchanged since I wrote Design for Community seven years ago.

Powazek’s seminal book is basically out of print at this point, only available via used book sellers starting at $50 a copy. But the 10 points he offers above are a great condensed version to get you started.

I’m hoping to use his ideas (and the book) to get things rolling (someday!) in my own shop in Anchorage.

And I’m still in the camp that believes your ability to serve your community — online or otherwise — will keep you alive whereas a mass media approach in which you teleport content in from other places won’t make it in the future.

UPDATE: Jeff Jarvis recounts the many examples in which the web community has responded to Garfield’s notes on comments. He links to no less than 8 cogent comments on commenting.

When the announcement went out about the cancellation of the Bryant Park Project, the comments on the NPR site numbered in the hundreds. The counts I saw stopped around 600, yet there may be more (who wants to count?).

When the announcement went out about the cancellation of the Bryant Park Project, the comments on the NPR site numbered in the hundreds. The counts I saw stopped around 600, yet there may be more (who wants to count?). The word is out that a little more than a week after launch, the iPhone 3G is now just plain gone from stores across the U.S. — be they Apple Stores or AT&T stores. Indeed, AT&T was sold out nationwide on the first day. Apple Stores have carried the device intermittently ever since and as of Monday morning there were only 3 stores nationwide that had anything — each carrying only one model.

The word is out that a little more than a week after launch, the iPhone 3G is now just plain gone from stores across the U.S. — be they Apple Stores or AT&T stores. Indeed, AT&T was sold out nationwide on the first day. Apple Stores have carried the device intermittently ever since and as of Monday morning there were only 3 stores nationwide that had anything — each carrying only one model. AOL Radio is pretty simple. It’s direct, live streaming access to the “AOL Radio” channels of music, sort of like satellite radio in that they aren’t local broadcast stations and are organized around tons of musical themes/styles. But it’s also an application that grants streaming access to hundreds of local terrestrial stations in the CBS collection. I can now listen, on the iPhone (with a live WiFi signal) to real-time streams of radio stations from coast to coast.

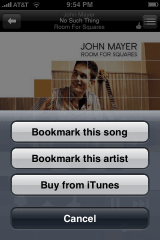

AOL Radio is pretty simple. It’s direct, live streaming access to the “AOL Radio” channels of music, sort of like satellite radio in that they aren’t local broadcast stations and are organized around tons of musical themes/styles. But it’s also an application that grants streaming access to hundreds of local terrestrial stations in the CBS collection. I can now listen, on the iPhone (with a live WiFi signal) to real-time streams of radio stations from coast to coast. Pandora had interested me before, but only in an intellectual way. Now, presented again on the iPhone for free, I figured I’d try it again. It’s amazing, especially over WiFi. Let me say that again: it’s amazing.

Pandora had interested me before, but only in an intellectual way. Now, presented again on the iPhone for free, I figured I’d try it again. It’s amazing, especially over WiFi. Let me say that again: it’s amazing. I’ve begun discovering music and artists again. I’ve started buying music again. Sunday alone I dropped $30 on new music, buying tracks both from the iTunes Store and from the Amazon MP3 Downloads service. All $30 were spent on artists I’d never experienced before Pandora suggested them and I bought them using links presented by Pandora.

I’ve begun discovering music and artists again. I’ve started buying music again. Sunday alone I dropped $30 on new music, buying tracks both from the iTunes Store and from the Amazon MP3 Downloads service. All $30 were spent on artists I’d never experienced before Pandora suggested them and I bought them using links presented by Pandora. Perhaps I’m already past the age where music radio makes sense for me, but I have to wonder what happens to music radio when this kind of access to music is virtually ubiquitous. Remember — the iPhone 3G sold 1 million devices in the first weekend and is sold out nationwide a week later. Pandora is a free service and free application — no advertising, no tricks — and it’s easy to use. (I began to wonder why I bothered syncing music to the iPhone — why not just live on Pandora recommendations alone?)

Perhaps I’m already past the age where music radio makes sense for me, but I have to wonder what happens to music radio when this kind of access to music is virtually ubiquitous. Remember — the iPhone 3G sold 1 million devices in the first weekend and is sold out nationwide a week later. Pandora is a free service and free application — no advertising, no tricks — and it’s easy to use. (I began to wonder why I bothered syncing music to the iPhone — why not just live on Pandora recommendations alone?)