The word is out that a little more than a week after launch, the iPhone 3G is now just plain gone from stores across the U.S. — be they Apple Stores or AT&T stores. Indeed, AT&T was sold out nationwide on the first day. Apple Stores have carried the device intermittently ever since and as of Monday morning there were only 3 stores nationwide that had anything — each carrying only one model.

The word is out that a little more than a week after launch, the iPhone 3G is now just plain gone from stores across the U.S. — be they Apple Stores or AT&T stores. Indeed, AT&T was sold out nationwide on the first day. Apple Stores have carried the device intermittently ever since and as of Monday morning there were only 3 stores nationwide that had anything — each carrying only one model.

This is bad for music radio.

Okay, a bit over the top, but stay with me…

When the iPhone 2.0 software came out (which works on the old phones, not just the new sold-out ones), I dutifully downloaded and installed it on my own iPhone. Much of the system was unchanged. But the arrival of the App Store made all the difference, allowing the download and installation of applications that extend the functionality of the iPhone.

Two applications in particular were fascinating, in the context of broadcasting. One was AOL Radio, the other Pandora. Both of these services have existed at least for a few years online. But these are the first examples of full-bodied mobile implementations.

AOL Radio

AOL Radio is pretty simple. It’s direct, live streaming access to the “AOL Radio” channels of music, sort of like satellite radio in that they aren’t local broadcast stations and are organized around tons of musical themes/styles. But it’s also an application that grants streaming access to hundreds of local terrestrial stations in the CBS collection. I can now listen, on the iPhone (with a live WiFi signal) to real-time streams of radio stations from coast to coast.

AOL Radio is pretty simple. It’s direct, live streaming access to the “AOL Radio” channels of music, sort of like satellite radio in that they aren’t local broadcast stations and are organized around tons of musical themes/styles. But it’s also an application that grants streaming access to hundreds of local terrestrial stations in the CBS collection. I can now listen, on the iPhone (with a live WiFi signal) to real-time streams of radio stations from coast to coast.

Since the iPhone goes everywhere with you, and given the near-ubiquity of WiFi signals, I now have hundreds of radio stations in my pocket. Sure, you could manage this before with several workarounds, but this is no workaround — this is a real implementation of a terrestrial transmitter threat that’s easy to use for mere mortals.

But that’s just AOL Radio. Forget that. That’s a threat we can obviate by getting our signals on the iPhone, too (not too hard — it’ll be done soon, I’m sure). Let’s get it on with Pandora.

Pandora

Pandora had interested me before, but only in an intellectual way. Now, presented again on the iPhone for free, I figured I’d try it again. It’s amazing, especially over WiFi. Let me say that again: it’s amazing.

Pandora had interested me before, but only in an intellectual way. Now, presented again on the iPhone for free, I figured I’d try it again. It’s amazing, especially over WiFi. Let me say that again: it’s amazing.

A huge library of songs, all gathered for you with the backing of the Music Genome Project. You pop in a favorite album, artist or song and Pandora generates a complete “station” for you of music from that artist and stuff that’s musically similar to the album/artist/song you’ve identified. And it works.

Let me say that again, too: IT WORKS.

What’s surprising is the sheer speed in which tracks pop down to the iPhone and start playing. If you skip ahead the next track pops up nearly as fast as your CD player would find something further down the disc platter. Oh, and the audio quality is easily equal to good FM (over WiFi — less so over 3G or EDGE networks).

I’ve begun discovering music and artists again. I’ve started buying music again. Sunday alone I dropped $30 on new music, buying tracks both from the iTunes Store and from the Amazon MP3 Downloads service. All $30 were spent on artists I’d never experienced before Pandora suggested them and I bought them using links presented by Pandora.

I’ve begun discovering music and artists again. I’ve started buying music again. Sunday alone I dropped $30 on new music, buying tracks both from the iTunes Store and from the Amazon MP3 Downloads service. All $30 were spent on artists I’d never experienced before Pandora suggested them and I bought them using links presented by Pandora.

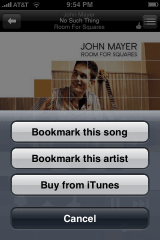

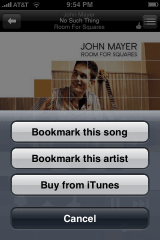

And get this… if the track or album is available on iTunes, you can buy it wirelessly right on the iPhone, no computer required.

Your own music discoveries can be broad or narrow based on how your “stations” are created and configured (which sounds a lot harder than it really is). And you can combine your stations into mix stations, granting you access to more eclectic recommendations.

Then there are more features on the regular Pandora web site. You can do the same thing via the full web that you do on the iPhone, but there are mild social networking features, extending the recommendation engine further. Plus, for more complex “station” operations, the full web site offers better tools. But it’s all one account, synchronized instantly back and forth as you use the service anywhere.

Why Listen to Music Radio?

Perhaps I’m already past the age where music radio makes sense for me, but I have to wonder what happens to music radio when this kind of access to music is virtually ubiquitous. Remember — the iPhone 3G sold 1 million devices in the first weekend and is sold out nationwide a week later. Pandora is a free service and free application — no advertising, no tricks — and it’s easy to use. (I began to wonder why I bothered syncing music to the iPhone — why not just live on Pandora recommendations alone?)

Perhaps I’m already past the age where music radio makes sense for me, but I have to wonder what happens to music radio when this kind of access to music is virtually ubiquitous. Remember — the iPhone 3G sold 1 million devices in the first weekend and is sold out nationwide a week later. Pandora is a free service and free application — no advertising, no tricks — and it’s easy to use. (I began to wonder why I bothered syncing music to the iPhone — why not just live on Pandora recommendations alone?)

I’m curious if any music station programmers out there have a take on Pandora they’d like to share. I know there are things you can do with radio that Pandora will never match. And I know the Pandora catalog is limited by the licensing deals they can strike with publishers. But really… if you can listen to “stations” tailored to your preferences and discover new-to-you music in a hyper-efficient way, why turn to terrestrial radio for music at all?

If you’re human-hosting your music, you’d better be doing a better job than the Music Genome Project.

The word is out that a little more than a week after launch, the iPhone 3G is now just plain gone from stores across the U.S. — be they Apple Stores or AT&T stores. Indeed, AT&T was sold out nationwide on the first day. Apple Stores have carried the device intermittently ever since and as of Monday morning there were only 3 stores nationwide that had anything — each carrying only one model.

The word is out that a little more than a week after launch, the iPhone 3G is now just plain gone from stores across the U.S. — be they Apple Stores or AT&T stores. Indeed, AT&T was sold out nationwide on the first day. Apple Stores have carried the device intermittently ever since and as of Monday morning there were only 3 stores nationwide that had anything — each carrying only one model. AOL Radio is pretty simple. It’s direct, live streaming access to the “AOL Radio” channels of music, sort of like satellite radio in that they aren’t local broadcast stations and are organized around tons of musical themes/styles. But it’s also an application that grants streaming access to hundreds of local terrestrial stations in the CBS collection. I can now listen, on the iPhone (with a live WiFi signal) to real-time streams of radio stations from coast to coast.

AOL Radio is pretty simple. It’s direct, live streaming access to the “AOL Radio” channels of music, sort of like satellite radio in that they aren’t local broadcast stations and are organized around tons of musical themes/styles. But it’s also an application that grants streaming access to hundreds of local terrestrial stations in the CBS collection. I can now listen, on the iPhone (with a live WiFi signal) to real-time streams of radio stations from coast to coast. Pandora had interested me before, but only in an intellectual way. Now, presented again on the iPhone for free, I figured I’d try it again. It’s amazing, especially over WiFi. Let me say that again: it’s amazing.

Pandora had interested me before, but only in an intellectual way. Now, presented again on the iPhone for free, I figured I’d try it again. It’s amazing, especially over WiFi. Let me say that again: it’s amazing. I’ve begun discovering music and artists again. I’ve started buying music again. Sunday alone I dropped $30 on new music, buying tracks both from the iTunes Store and from the Amazon MP3 Downloads service. All $30 were spent on artists I’d never experienced before Pandora suggested them and I bought them using links presented by Pandora.

I’ve begun discovering music and artists again. I’ve started buying music again. Sunday alone I dropped $30 on new music, buying tracks both from the iTunes Store and from the Amazon MP3 Downloads service. All $30 were spent on artists I’d never experienced before Pandora suggested them and I bought them using links presented by Pandora. Perhaps I’m already past the age where music radio makes sense for me, but I have to wonder what happens to music radio when this kind of access to music is virtually ubiquitous. Remember — the iPhone 3G sold 1 million devices in the first weekend and is sold out nationwide a week later. Pandora is a free service and free application — no advertising, no tricks — and it’s easy to use. (I began to wonder why I bothered syncing music to the iPhone — why not just live on Pandora recommendations alone?)

Perhaps I’m already past the age where music radio makes sense for me, but I have to wonder what happens to music radio when this kind of access to music is virtually ubiquitous. Remember — the iPhone 3G sold 1 million devices in the first weekend and is sold out nationwide a week later. Pandora is a free service and free application — no advertising, no tricks — and it’s easy to use. (I began to wonder why I bothered syncing music to the iPhone — why not just live on Pandora recommendations alone?) Earlier this week I was advised privately to wait for an announcement from NPR about BPP — without any hint of what said announcement might be — and I’m still waiting. I’d love to hear NPR announce a bold new plan to take the BPP straight to the web and change it up somehow. If anyone would care to shed additional light, I’m all ears (as are about

Earlier this week I was advised privately to wait for an announcement from NPR about BPP — without any hint of what said announcement might be — and I’m still waiting. I’d love to hear NPR announce a bold new plan to take the BPP straight to the web and change it up somehow. If anyone would care to shed additional light, I’m all ears (as are about

One of my favorite writers on matters of strategy, especially related to technology application in business, is Bob Lewis, a long-time columnist from

One of my favorite writers on matters of strategy, especially related to technology application in business, is Bob Lewis, a long-time columnist from