NOTE: Updates added at the bottom of the post.

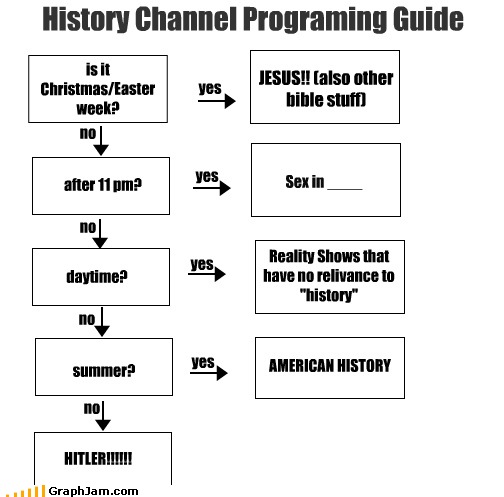

Late last week the host of a major PBS program took aim, in a pseudo-blog-post, at NYU journalism professor and innovator Jay Rosen because Rosen said he didn’t like that hosts’s program — a weekly talking-heads affair based out of Washington, DC.

Late last week the host of a major PBS program took aim, in a pseudo-blog-post, at NYU journalism professor and innovator Jay Rosen because Rosen said he didn’t like that hosts’s program — a weekly talking-heads affair based out of Washington, DC.

I won’t link to the host or their complaint here because they didn’t bother to link to Rosen’s original piece in the Washington Post or his blog or his fascinating Twitter feed. And that host was deliberately ignorant of Rosen’s work, failing to do a shred of research. They didn’t even watch a video of Rosen appearing on PBS a little over a year ago.

But I will link to that insightful Jay Rosen appearance on PBS — with the now-retired Bill Moyers — in which he specifically critiqued the problem of Washington insider journalism, including the many insiders that appear on the outraged host’s program every week (I would have embedded the video here, but the video isn’t embeddable without stealing it). I encourage you to watch, despite the length, because Rosen shares a highly nuanced view of Washington journalists, politicians and their mutual interest in preserving status quo power.

In the reaction to Rosen’s appeal to put this particular insider show out to pasture, the host’s post (yeah, I know this is tedious, but I’m making a point) never referred to Rosen by name, never linked to anything he’s done, including the source article that ticked off the host in the first place, never addressed Rosen’s concerns and in fact reinforced his long-standing critique of beltway insider gamesmanship.

Only calling Rosen “the NYU professor” and failing to link to the source piece is an intentional slap in the face from an elder in what Rosen calls the “Church of the Savvy.” Dismissing his argument simply reinforces his point: that this program, the host and its guests are beltway insiders talking shop rather than helping the public hold politicians to account in meaningful, public-service ways. The host’s total mischaracterization of Rosen’s arguments also proves the prediction that beltway insiders reflexively dismiss outsiders, thus retaining their positions.

I defend anybody’s right to comment on the news of the day – whether it is Chris Matthews or Bill O’Reilly or Larry King or Jon Stewart. I even defend the NYU professor, however misguided he might be.

<sarcasm>How generous of you. Thank God you’re standing up for Jay Rosen’s free speech rights! And you know, you’re right… Bill O’Reilly and Jay Rosen are cut from the same cloth, aren’t they?</sarcasm>

In effect, the host played directly into Rosen’s analysis. But worse, the show’s audience has been denied a serious discussion about the mission of such programs. There may be valid reasons for having an insider show, perhaps as part of a larger programming strategy, but the claim that the show “saves marriages” (I’m not making that up — that’s in the reaction post) is utterly unserious and demonstrates the intense contempt this insider has for meaningful media criticism from a serious and even credentialed source.

What to do?

Look, I’m not on the “cancel this show” bandwagon. It makes viewers happy, which helps bring in the bucks. And for a talking head show, it’s a considerable step above what you get on cable channels. But the demonization of Rosen is breathtakingly ignorant and/or deliberately dismissive at a level unbecoming of a PBS-sanctioned “journalism” host.

I don’t think an apology is in order. I think the next show should have Rosen on as a guest. If you’re not a guardian of the Church of the Savvy, you’ve got nothing to fear. Bill Moyers didn’t shy away from this issue, why should you? And hey — this could be the equivalent of Jon Stewart appearing on CNN’s Crossfire.

Be More: Resourceful

[1] Here’s a brief example (video) of how “savviness” cuts off legitimate debate in the professional press:

http://www.youtube.com/v/ms548AkFP5s&hl=en_US&fs=1&rel=0

[2] And here’s a little more on what savviness is, directly from Jay Rosen.

[3] Meanwhile, if you like talking head shows examining national politics, forget the snoozy Friday evening PBS fare and go for something more entertaining and at least a little further outside the beltway. I highly recommend Slate’s Political Gabfest (also entertaining on Facebook), which has only 1 beltway insider (who also has appeared on the aggrieved host’s show). If you must stick to public media sources, go for Left, Right and Center, which has insiders, but at least it’s from California.

[4] And about linking… Why didn’t the host link to Rosen’s original piece at the Washington Post? Because the host was obeying old-media rules, in addition to being dismissive. Rosen explains the rules in this discussion of outbound linking:

http://www.youtube.com/v/RIMB9Kx18hw&hl=en_US&fs=1&rel=0

[5] And if you’ve never seen it, here’s the Jon Stewart appearance on Crossfire that pretty much ended the show. It exposed this extreme Church-of-the-Savvy example for what it was:

http://www.youtube.com/v/aFQFB5YpDZE&hl=en_US&fs=1&rel=0

UPDATE 1: There’s another great Jay Rosen piece, in which he refers to the unnamed PBS program: Audience Atomization Overcome: Why the Internet Weakens the Authority of the Press. And in this piece, he goes on to explain some concepts about how the mainstream press — especially the insiders — defines what ate and aren’t legitimate news and discussion points for consideration in public life.

UPDATE 2: One of my favorite firebrands, Michael Rosenblum, took our subject to task in a seething post that posits our dear host as a member of a doomed noble class.