Do you remember the Apple II series of personal computers? I certainly do. I got my first one in January 1983 (the Apple IIe) and it was a revelation. Back then the Apple II dominated the personal computer space (IBM was just introducing the first IBM PC). It was a serious cash cow for the new wonders of Silicon Valley: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.

Do you remember the Apple II series of personal computers? I certainly do. I got my first one in January 1983 (the Apple IIe) and it was a revelation. Back then the Apple II dominated the personal computer space (IBM was just introducing the first IBM PC). It was a serious cash cow for the new wonders of Silicon Valley: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.

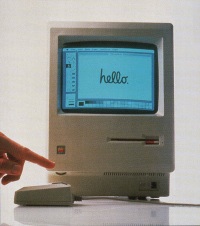

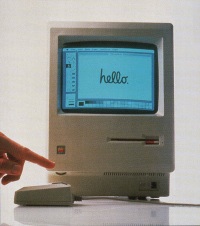

But even in 1983, in the peak of this tremendous success, Apple was reinventing the personal computer. They were secretly inventing the Macintosh, which was introduced a year after I got that Apple IIe in January 1984 (with the famous Superbowl ad).

Developing the Mac was a massively expensive proposition. New chips, new software, new case designs, a mouse, even a brand new 3.5″ floppy drive developed by Sony but still considered cutting-edge and risky. Everything called for clean slate development in order to get it all just right.

So what funded this engineering miracle? The successful and highly profitable Apple II series. And guess what — the Mac wasn’t profitable at launch. That first year was deadly. Apple introduced a $2,500 computer ($5,100 in 2007 dollars) that had two software programs: MacPaint and MacWrite, and it wasn’t compatible with the growing library of Apple II software titles.

Check out this brief video (43 seconds) of Guy Kawasaki recounting how the Mac team was funded by the Apple II team, and the considerable tension this created:

I often think of the Apple II / Macintosh example when conversations in public media circles turn to the question of how will we pay for this new media stuff that doesn’t make any money and takes money out of the profitable broadcasting business. Newspapers and the music industry are also great analogies for public broadcasting.

It takes real leadership, real courage to deliberately take cash from a profitable and successful unit and sink it into the next big thing, even if it takes years for it to pay off. Plus, you have to deal with the political pressures to stop funding this financial black hole from the “reasonable” business people all around you (on the board, on the management team, in the community, on the staff). As I look at my own public media business today, we’ve not even begun to seriously tackle the challenges of the new media world — chiefly because “Apple II” folks are in charge. I often wonder whether we should give up trying to reform the core of the company (a la Ideastream) and simply fund an external unit that can focus on the new media challenge without interference from the traditional “cash cow” part of our business.

The one example of “put it outside the core” I know of in the public media world can be found at Chicago Public Radio. Their Vocalo project (as described by Robert Paterson), is an external unit in every sense of the word. They have separate facilities, a new name unaffiliated with the old name, a separate budget, different leadership, different content and business models, etc. It’s a fascinating approach, and it mimics the Apple experience.

But I’m wondering… is anyone else in public media doing this? Who else, if anyone, is creating distinct subsidiaries for innovation? Is anyone else willing to spend their Apple II money on their Macintosh project?

I have no vested interest the “old order” of journalism, be it at newspapers, in public radio or elsewhere. I don’t have a journalism degree (though I do have the kissing cousin degree: English). I’ve collected a paycheck from the media world for less than 4 years now, having spent many years before that in a variety of businesses.

I have no vested interest the “old order” of journalism, be it at newspapers, in public radio or elsewhere. I don’t have a journalism degree (though I do have the kissing cousin degree: English). I’ve collected a paycheck from the media world for less than 4 years now, having spent many years before that in a variety of businesses.

Geeks out there probably know Leo Laporte, the long-time commercial radio and TV host, made especially well-known via the now-defunct TechTV cable channel. He continues to develop media, having built the

Geeks out there probably know Leo Laporte, the long-time commercial radio and TV host, made especially well-known via the now-defunct TechTV cable channel. He continues to develop media, having built the

Do you remember the Apple II series of personal computers? I certainly do. I got my first one in January 1983 (the Apple IIe) and it was a revelation. Back then the Apple II dominated the personal computer space (IBM was just introducing the first IBM PC). It was a serious cash cow for the new wonders of Silicon Valley: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.

Do you remember the Apple II series of personal computers? I certainly do. I got my first one in January 1983 (the Apple IIe) and it was a revelation. Back then the Apple II dominated the personal computer space (IBM was just introducing the first IBM PC). It was a serious cash cow for the new wonders of Silicon Valley: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.