I’m so glad the newspaper industry is blazing the trail to either self-transformation or self-immolation in this new media world. Public media companies are being given a very close look at an industry in gut-wrenching transformation just before our own will undergo the same. The trail before us has been blazed, and we should be thankful.

Recently in Online Journalism Review, Robert Niles wrote a great link-bait article — It’s time for the newspaper industry to die — in which he explains why newspapers need to dump the word “newspaper” from their internal lexicon and psychology. He offers several reasons for this.

But the best reason centers on that favorite word of mine: Community. And the reason applies to public media, too.

Niles recognizes a fundamental shift in newspapers over the last decade: they’ve cut back on real community service while maximizing shareholder profits.

Great content and great tools are not enough to build the large, habitual audience that content publishers will need to maximize their opportunities to make money online, through advertising and sales. Even more than those two things, a website needs great engagement with its readers. And engagement with the public is something that’s been budgeted out of too many newsrooms over the past generation.

It’s time to bring that back. It’s time to do that online. And if a beloved label needs to be sacrificed to inspire the innovation that will enable this effort, so be it. It’s time for the “newspaper” industry to die. Because we all need the news industry to survive.

I would submit the term “public broadcasting” can take the same route to oblivion. One-way broadcasting can no longer be the point, even if that’s the most comfortable thing to do. Community engagement, public service, gathering, convening, whatever — that’s got to be the goal. Broadcasting is a tool, a means to an end of public service.

What we want from a “newspaper” isn’t fish wrapping or bird cage lining, it’s news, information, connection to events. What we want from broadcasting is pretty similar. But let’s not confuse the delivery system with the purpose. And let’s not believe for a moment that retransmitting someone else’s non-local, marginally-relevant content is something worth preserving in a world of on-demand access to all content anywhere.

—

Since entering the public media world professionally almost four years ago, I’ve always thought the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) was ripe for transformation (and not because of that Bush administration weasel Kenneth Tomlinson). Why? Because they need a name change and a mission reevaluation. It’s too bad the purpose of the CPB — funding and fostering public Broadcasting — has its instructions enshrined in law. It’s making it difficult, if not impossible, to fund new projects. Consider this Q&A between IMA’s Mark Fuerst and CPB’s current president, Pat Harrison, at the recent IMA 2008 conference in Los Angeles (audio clip, about 1 minute):

[audio:https://gravitymedium.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/harrison-on-funding2.mp3%5DHarrison gets it. Sure, she’s referring to reauthorization for CPB in Congress, but that’s just cover for avoiding talk about shifting funding out of pure broadcasting and into community engagement. (In fairness, the CPB has spent millions over the past several years on new media research and projects, but as I’ve noted before, we haven’t really seen any transformations.)

This is really too bad. Because while newspapers are stuck with an old term and a psychology that’s hard to shake, we have those challenges plus actual laws that govern a significant portion of our funding. To change the laws or create new ones to foster and fund community building and interaction via all available media may be politically impossible.

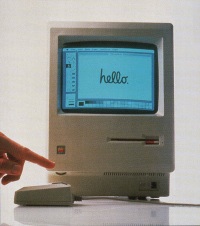

Do you remember the Apple II series of personal computers? I certainly do. I got my first one in January 1983 (the Apple IIe) and it was a revelation. Back then the Apple II dominated the personal computer space (IBM was just introducing the first IBM PC). It was a serious cash cow for the new wonders of Silicon Valley: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.

Do you remember the Apple II series of personal computers? I certainly do. I got my first one in January 1983 (the Apple IIe) and it was a revelation. Back then the Apple II dominated the personal computer space (IBM was just introducing the first IBM PC). It was a serious cash cow for the new wonders of Silicon Valley: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.