Pop quiz, hotshot. There’s a bomb on a bus. Once the bus goes 50 miles an hour, the bomb is armed. If it drops below 50, it blows up. What do you do? What do you do?

One of my favorite writers on matters of strategy, especially related to technology application in business, is Bob Lewis, a long-time columnist from InfoWorld and a popular business consultant as well. He writes a weekly column, shared via the web. Great stuff.

One of my favorite writers on matters of strategy, especially related to technology application in business, is Bob Lewis, a long-time columnist from InfoWorld and a popular business consultant as well. He writes a weekly column, shared via the web. Great stuff.

This week he wrote a piece (the second in a series) on business strategy: “A business change cornucopicolumn.” And it sounds like he’s talking about my specific public media company in Anchorage and the public media industry in general.

It’s spooky.

Check out this rather heavy quotation (sorry, I just had to) and see if it fits your strategic situation (added boldface is mine):

[Let’s] start with a framework for describing any business. It has ten dimensions — five external, five internal.

The external dimensions are:

- Customers: The people who make buying decisions about what the company has to sell.

- Product: What the company sells its customers.

- Price: What the company charges for its products, along with margin goals, contract terms and conditions and so on.

- Marketplace: The business ecosystem — suppliers, distribution channel, competitors and partners.

- Messages: How the business explains itself and its products.

The internal dimensions are:

- People: Employees and contractors — the human [beings] themselves, their skills, knowledge and experience.

- Process: How people do the company’s work.

- Technology: The tools people use when fulfilling their roles in the company’s processes.

- Structure: How the company is organized — its reporting structure, [salary] structure, policies and guidelines, and internal communications.

- Culture: How employees respond to common situations.

In healthy organizations, the ten dimensions are consistent, interconnected, and mutually reinforcing.

Companies don’t undertake strategic change just because one or two are a bit moldy. They undertake it … because the company’s business model no longer works. Perhaps the company’s products are no longer relevant, or the customer segment it serves is shrinking, or its pricing is no longer competitive in its marketplace, or its marketplace has changed in some serious way. It’s fallen behind.

…

Many companies enter a sort of vegetative state in which doing nothing at all becomes the strategy — they pare spending down beyond the minimum, hoping someone buys them before they’re completely [beat]. The alternative, though, is nearly as bad, because there is no such thing as changing just one of the ten dimensions of organizational design.

…

[For example:] Your competitive challenge is pricing. But you can’t change just the price. You need a [better] response than that, because … you’ll lose money on every transaction.

To cut prices while preserving margins you’ll need to change your processes. That means “changing” your people in some way too, because new processes wholly or partially invalidate old skills.

Most likely, you’ll have to change structure and culture as well, and reposition yourself in the marketplace (including, perhaps, bypassing your current distribution channel). All of which will require significant changes in technology.

That’s a lot to change all at once. You have to take an interconnected ten-dimensional model of the business that worked and redesign it into a new interconnected ten-dimensional model of the business that works.

Then you bet the farm, implementing the new organizational design as one massive process. And you don’t get to stop running your business during the change-over.

…[The] company’s executive team decides the basic shape of pricing goals, production strategy (process), and distribution. It also decides on any structural changes that will be required, putting the right people in charge of critical business responsibilities.

And, it will define the underlying cultural changes necessary for everything else to work.

The executive team will focus its attention on the cultural change. The rest of the company will use the 3-1-3-4 formula (3-year vision / 1-year strategy / 3-month goals / 1-week plan) to figure out everything else and make it happen in manageable increments.

Holy shmoly!

I don’t know about your company, but that fits my company, right this second, perfectly.

We’re grappling with these problems all at once:

- Public TV’s audience is dwindling nationally and locally. That reduces advertising (sponsorship!) revenue potential and revenue actuals.

- TV membership dollars are steady, but from a shrinking number of donors (per donor giving is up, total donor count is falling).

- The cost of producing national-quality mass-media-style pubTV programming has risen beyond our ability to do it locally and it’s quickly becoming too expensive to buy it in national packs from PBS.

- The cost of producing lower-end media has collapsed, allowing a flood of programming at the bottom-end of the market, and allowing the “audience” to produce (and consume) their own digital media, without paid gatekeepers like us.

- Our TV fundraising model is based upon transactions with people that don’t usually like us or give us money — we sell them stuff. In so doing, we’ve painted ourselves into a corner: true believers hate us when we grab the money and cut off their favorite programs, yet we need that cash to pay for the true believer programs. When we attempt to raise money around regular programs, they tank, financially.

- Our public radio audience has grown over the past 15 years, but has now flattened and may be starting a long backward slide if we can’t figure out how to grow our audience further or deepen our relationship with the audience we’ve got.

- Our staff is composed almost exclusively of baby boomers and others that built and/or grew up with the public media system. They are approaching retirement and don’t seem to have another “revolution” in them. Internet models are curious, but unproven, for them, and since they largely eschew new media consumption models, they don’t know how to approach them from a business angle.

- Government funding for public media in our state has fallen over the past 15 years. Using inflation-adjusted dollars, funding has dropped by more than 50% in 10 years. Plus, companies successful with fundraising activities are deliberately cut off from state funding. And federal funding has been flat or declining (in inflation-adjusted dollars).

- Our strategic drift has led to an accumulation of drifting employees and a loss of innovating ones. If you’re a striver, a pusher, a mover-and-shaker, if you want to accomplish something, we offer a frustrating environment at best. Our culture says we should wait for a knight in shining armor to come along with bags of money a new and exciting crusade to save us.

- Our product set, as currently deployed, does not compete well enough in a mass market well enough to draw the required revenue, and it doesn’t serve a niche market well enough to garner a rabid following of local support. In web terms, we’re too small to be Google, but too big to be 37signals. (What’s the opposite of a sweet spot?)

I could go on.

Our CEO has repeatedly likened our strategic situation to changing the tires on a bus while driving down the highway at 60 miles per hour. That feels about right.

Personally, I’d like to pull over, get this bus up on a lift and change the tires in a more controlled environment. Then we can get back on the road. But as soon as we drop below 50mph — KABOOM! …the bus explodes, and that’s it for Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock.

Which is why Bob Lewis’ 3-1-3-4 formula may be required for us on the mobile pit crew. And it’s why strategies built around a new understanding of the 10 dimensions of business are in order. Clearly, more than 1 or 2 of the 10 dimension have changed:

- Our customers are moving online and expect on-demand access in addition to the streamed services. They also want to interact with us. (Ironically, in a hyper-connected world, they’re more “disconnected” than ever — they need more connection with people like us, people like themselves, people in their neighborhoods.)

- Our marketplace has changed; it’s no longer “3 networks + PBS” and hasn’t been for years. And it’s getting worse as new platforms appear and the audience fractures.

- Pricing models have evolved dramatically as the scarcity economic model dissipates in media markets.

- Our people and processes were selected for legacy customers and markets, not the present day; they need to be retrained technologically and culturally or be replaced.

- Our legacy technology is prohibitively expensive to maintain, doesn’t offer sufficient economic advantage and prevents investment in new technology that would enable new processes and services.

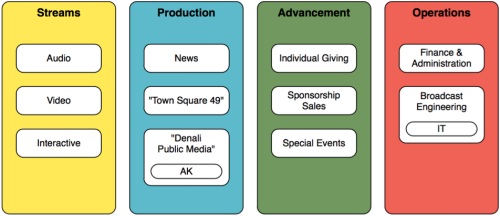

- Our business structures and company cultures are unfocused at best and self-destructive at worst. We focus on “radio” and “TV” and “web” and we promote history over innovation. We need a culture that encourages and develops the best of what our public media “tribe” seeks to experience.

Can we still turn it around? I don’t know. Perhaps in smaller companies with a few lucky lightning strikes of vision and a philanthropic community that supports a positive vision of the future (a vision we must articulate). Or maybe in the largest companies with deeper pockets and tighter links to market forces.

We’re at the cusp of turning it around in Anchorage. Or at least I think so — I hope so. There’s still a great deal of fearless, tireless and perhaps even foolhardy leadership required. We might just have the kernel of what it takes. I think the rest of 2008 will likely set us up for ultimate success or failure. We’ll either get this right quickly or it will likely be too late to recover.

How are you doing with your public media bus?

One of my favorite writers on matters of strategy, especially related to technology application in business, is Bob Lewis, a long-time columnist from

One of my favorite writers on matters of strategy, especially related to technology application in business, is Bob Lewis, a long-time columnist from  Geeks out there probably know Leo Laporte, the long-time commercial radio and TV host, made especially well-known via the now-defunct TechTV cable channel. He continues to develop media, having built the

Geeks out there probably know Leo Laporte, the long-time commercial radio and TV host, made especially well-known via the now-defunct TechTV cable channel. He continues to develop media, having built the